There is something scammy about Tim Ferriss. It might be how he made his initial windfalls: selling BrainQuicken and the 4-Hour Workweek. The former is essentially snake oil, and the latter is about using loopholes in the global economy to push work to others (IOW, it fails the business version of the moral imperative.)

But there is also something authentic about Ferriss. His desire to learn and to share his learnings is obvious. I think he would probably be doing the same things he's doing now if he lived in a post-scarcity society. Tools of Titans is a distilled version of the learning and sharing and while I want to skeptically say it is just a money grab by skimming Ferriss' podcasts, it is more than that.

The book can best be read like a daily devotional. Each podcast guess has 1-10 pages devoted to their best ideas and thoughts or their "tools". These can be trite, but as you will likely note, a lot of "trite" advice turns out to be the best. As Sam Harris points out, "On one level, wisdom is nothing more than the ability to take your own advice." If nothing else, Tools of Titans will be a guide to figuring out how to take your own advice.

At times, some of the advice is contradictory- wake up at 4:45, wake up whenever you want to, wake up early, wake up early and stand out in the sun nake. Use the Inbox Zero principle, use social media to make 1000 hardcore fans, but also never check your email and get off social media. This contradiction might be helpful, though: you don't have to emulate all of these "titans" if you want to find some modicum of happiness or success.

Instead, the questions Tim asks of his friends and peers get turned around to the reader: What would you write on a billboard in a major city? What are you doing to be healthy? What books do you suggest or give? (do you suggest or give books?) What would you tell your 20, 30-year-old self?

Why are you still drinking Coke? You know that shit is awful for you.

Sunday, March 19, 2017

Thursday, March 16, 2017

Review: The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

It is really tempting to explain things in terms of one or two factors, especially politics. I've been guilty of it myself; I've written "it's geography, stupid!" more times than I'd like to say. Yet, simplifying explanations of history, society, and government tend to be tools of evil (or stupidity). In the past, Christianity and Catholicism were used to explain imperialism under the guise of the White Man's Burden. The Nazi Reich based their explanations of the history of the world through racial differences and genetics. And today, we see the rising spectre of religious and racial hatred in the alt-right movements in Europe and the United States. We see people (close to our President!) putting history as a battle of "Christianity" versus "Islam" and "the White Man" versus "The Colored Man".

You also see some simple, not evil answers too. For example, somebody somewhere said something about guns and germs and steel explaining why some societies developed while other failed to. And while that certainly seems like a reason that the Americas failed to develop while Eurasia had millennia old states, it doesn't explain why some states became modern since they were freed from imperialism and while other states simply fell apart.

Fukuyama, in The Origins, is described the origin of the state and political order to set context for his book... Political Order. To do this he brings out all the major social sciences that he can: anthropology, sociology, demography, geography, economics and, of course, history. This makes what is essential/The best AP World History book (that won't get you a 5) ever/.

The history starts some six million years ago, while humanity was breaking off from our primate cousins, continues with the increasingly complicated relationship between families, tribes, and clans and ultimately culminates in the first state: imperial China. From Imperial China, we move west, to India, and then the Middle East, where we finally get to Europe to explore how the different histories of democracy unfolded until we get to the French Revolution.

In each location, we get another piece of the puzzle to what makes a state a /good/ state. China, for example, was the first that was able to subdue the social human animal:

Fukuyama considers a major factor and signal of political decay to be "Patrimonialism", or the genetic predisposition we have as humans to favor our families (through kin selection) or those who have allied with us (through reciprocal altruism). We might, as non-scholars, simply call it "nepotism" or "letting your daughter hang out with you and foreign leaders." Time and time again, it becomes the state societies revert to, whether by weak political structure or overt attempts to build such a society.

However, some societies, like India never get past patrimonialism. India's caste system is hyper-patrimonialism, where the entire structure of the universe is devoted to making sure that resources stay within a family line. Meanwhile, patrimonialism is subdued by religion in the eruption of Islam and the concept of the umma, or in the Catholic Church's insistence on her marriage laws being taken seriously (which, incidentally, meant the Catholic Church would acquire more and more resources).

At the same time, religion allows there to be a highly developed rule of law: India, Western Europe, and the Muslim world all have a highly developed sense that their leaders are below God's law. Yet, in China or Russia (influenced by the Hordes) religion was subservient to the leader. Indeed, in China the religion never developed past ancestor worship!

This rule of law is necessary for a state to be both powerful and to be checked. It means that the state and its ruler is beholden to something greater than itself. That means, depending on the era, religion but it also means literally just legal constitutions. It is powerful enough to bind the warriors of India to the brahmin religious class above them... but also keep kings from massacring entire towns.

The third piece of political order is accountability. Accountability is built into our primeval social structures: if the Chieftan fails to be good, we just make somebody else Chieftan. You can literally look at the person while you do it. But as societies grow large, accountability disappears. It may arise, like in Eastern European kingdoms, where only certain portions of the noble class have any power over the ruler. Or it might fail to arise at all, as it did in China. Or even noble accountability might be squashed, as it was in France and Russia.

The balance of these three- rule of law, accountability, and a modern meritocratic state- are what make political order. They, in turn, are embattled and bolstered by a constellation of religion, patrimonialism, and secular values. What made Europe explosively imperial? Guns, germs and steel!

But other stuff, too.

You also see some simple, not evil answers too. For example, somebody somewhere said something about guns and germs and steel explaining why some societies developed while other failed to. And while that certainly seems like a reason that the Americas failed to develop while Eurasia had millennia old states, it doesn't explain why some states became modern since they were freed from imperialism and while other states simply fell apart.

Fukuyama, in The Origins, is described the origin of the state and political order to set context for his book... Political Order. To do this he brings out all the major social sciences that he can: anthropology, sociology, demography, geography, economics and, of course, history. This makes what is essential/The best AP World History book (that won't get you a 5) ever/.

The history starts some six million years ago, while humanity was breaking off from our primate cousins, continues with the increasingly complicated relationship between families, tribes, and clans and ultimately culminates in the first state: imperial China. From Imperial China, we move west, to India, and then the Middle East, where we finally get to Europe to explore how the different histories of democracy unfolded until we get to the French Revolution.

In each location, we get another piece of the puzzle to what makes a state a /good/ state. China, for example, was the first that was able to subdue the social human animal:

Fukuyama considers a major factor and signal of political decay to be "Patrimonialism", or the genetic predisposition we have as humans to favor our families (through kin selection) or those who have allied with us (through reciprocal altruism). We might, as non-scholars, simply call it "nepotism" or "letting your daughter hang out with you and foreign leaders." Time and time again, it becomes the state societies revert to, whether by weak political structure or overt attempts to build such a society.

However, some societies, like India never get past patrimonialism. India's caste system is hyper-patrimonialism, where the entire structure of the universe is devoted to making sure that resources stay within a family line. Meanwhile, patrimonialism is subdued by religion in the eruption of Islam and the concept of the umma, or in the Catholic Church's insistence on her marriage laws being taken seriously (which, incidentally, meant the Catholic Church would acquire more and more resources).

At the same time, religion allows there to be a highly developed rule of law: India, Western Europe, and the Muslim world all have a highly developed sense that their leaders are below God's law. Yet, in China or Russia (influenced by the Hordes) religion was subservient to the leader. Indeed, in China the religion never developed past ancestor worship!

This rule of law is necessary for a state to be both powerful and to be checked. It means that the state and its ruler is beholden to something greater than itself. That means, depending on the era, religion but it also means literally just legal constitutions. It is powerful enough to bind the warriors of India to the brahmin religious class above them... but also keep kings from massacring entire towns.

The third piece of political order is accountability. Accountability is built into our primeval social structures: if the Chieftan fails to be good, we just make somebody else Chieftan. You can literally look at the person while you do it. But as societies grow large, accountability disappears. It may arise, like in Eastern European kingdoms, where only certain portions of the noble class have any power over the ruler. Or it might fail to arise at all, as it did in China. Or even noble accountability might be squashed, as it was in France and Russia.

The balance of these three- rule of law, accountability, and a modern meritocratic state- are what make political order. They, in turn, are embattled and bolstered by a constellation of religion, patrimonialism, and secular values. What made Europe explosively imperial? Guns, germs and steel!

But other stuff, too.

Saturday, March 4, 2017

Review: Narconomics: How to Run a Drug Cartel

Wainwright skirts the topic throughout the book, but when he finally gets to the conclusion, it seems like it is just a formality: we need to fix the demand-side of the criminal drug industry in order to make any meaningful progress. He does this by laying out how drugs get from the Andean mountainside to the concrete jungle street corners and explaining the economics of each step in the process.

The book is kind of like one long Freakonomics podcast: here is a story of cocaine farmers, here is the story of an American heroin addict, and here is a story of why New Zealand has the best party drugs and so on. This is good! And every story has the subtext beneath it. When discussing government efforts to destroy the different plants that go into drugs, Wainwright points out that cartels act like monoposonies- like Walmart- and they push the new cost of government interference onto suppliers. This is a pattern we see throughout the book: here is an area of the drugs trade, here is what government is doing to limit supply, and oh look it doesn't matter.

Many of America's problems (illegal immigration, gang violence, racial disparities in imprisonment, and the heroin epidemic) can all be solved by comprehensive drug reform. Unfortunately, Wainwright doesn't give the public much advice on where to go.

Bernie 2020.

The book is kind of like one long Freakonomics podcast: here is a story of cocaine farmers, here is the story of an American heroin addict, and here is a story of why New Zealand has the best party drugs and so on. This is good! And every story has the subtext beneath it. When discussing government efforts to destroy the different plants that go into drugs, Wainwright points out that cartels act like monoposonies- like Walmart- and they push the new cost of government interference onto suppliers. This is a pattern we see throughout the book: here is an area of the drugs trade, here is what government is doing to limit supply, and oh look it doesn't matter.

Many of America's problems (illegal immigration, gang violence, racial disparities in imprisonment, and the heroin epidemic) can all be solved by comprehensive drug reform. Unfortunately, Wainwright doesn't give the public much advice on where to go.

Bernie 2020.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

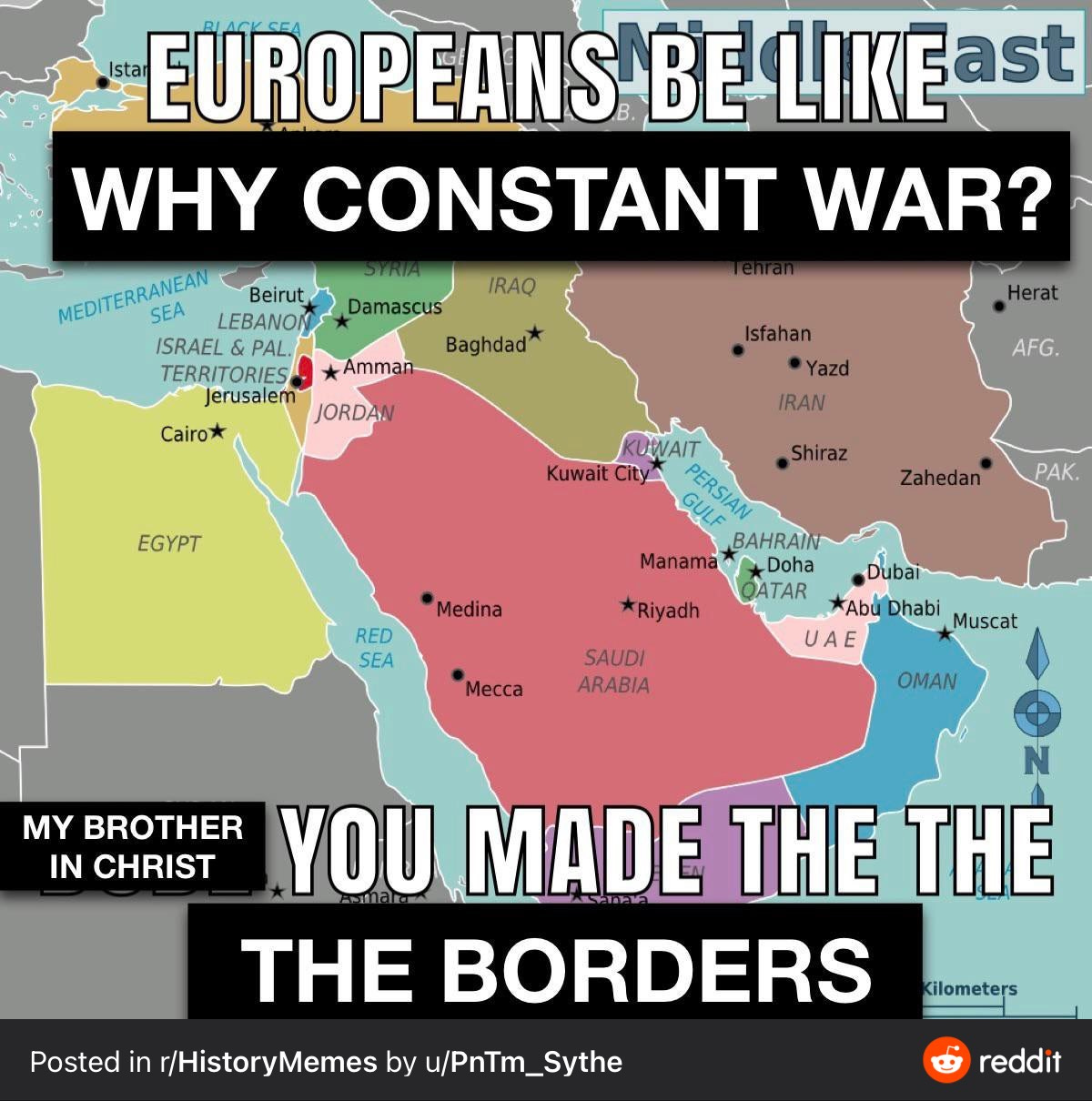

Review: Group Chat Meme

tl;dr: To endorse the concept that European borders are to blame for developing world conflict is to endorse problematic concepts of nationa...

-

I am intimately aware of the errors in my thoughts and the sins of my soul. I can hear the Type-A asshole screaming like a stolen mind in t...

-

People get the cosmic calendar wrong: The universe is not old. It is not old and wise and dirty. We tell that story to wrench dogmatic minds...

-

Uncommon Grounds is a great book, and points to what I think is an overlooked section of history: the history of things. We have lots of boo...