Most dystopian novels are about the relationship between power, knowledge, and meaning. 1984 and Brave New World are the two heavyweights in this area. In 1984, restricted knowledge gives the Party power and they have the ability to rewrite truth and control individual's ability to perceive meaning. Brave New World describes a world where meaning is annihilated by what we would now understand as unrestricted access to dopamine, and where power is no longer held by any individual: The System controls the world.

What the Handmaid's Tale does is propose a third instrument to orchestra power, knowledge and meaning: The Religion. I don't mean this as actual religion, but specifically as a psychological layer, an interface that exists between all interactions. In the Handmaid's Tale, it is clear that nobody in the novel is actually that devout to the Christian religion created by the Sons of Jacob. Rather, everybody is keeping up appearances.

In BNW and 1984, the main characters don't have that many friends or interactions. There are characters witnessed, and there are characters interacted with. 1984 has what? 3 interactive characters? BNW might have a few more, but in the Handmaiden's Tale there are many possible interactions: the Commander, Serena, the Marthas, Nick, Ofglen, Moira ... and these characters are all interacting with one another.

The Religion sits in between all of these characters managing, stifling and destroying different bonds. It regulates the flow of knowledge between different layers of society, and it acts against characters through these networks. How does The Religion do this despite nobody believing in it? (Literally, no character is unquestionably religious. Indeed, the religious that we do see are those oppressed- the Quakers, Catholics, Baptists and Jews. Anybody who has bought into The Religion, don't seem to have actually bought into all of its rules.)

What The Religion does to operate upon the characters is break down the trust that allows criticism of The Religion. On a societal level, it does this by just ending freedom of speech and shooting Women's Marchers. On an individual level, the Religion creates feelings of mutual distrust. This is most obviously seen in the relationship between Offred and Ofglen when they become aware of their mutual disdain for the Religion. In the eyes of each other and because of their mutual distrust, they were both pious. The Religion is then an n-player Prisoner's Dilemma, where defecting actually means freedom if enough players defect but mutual distrust prevents this defection.

With the Religion able to act on individuals through their networks, it is able to prescribe and deny meaning because ultimately meaning comes from our interactions. Neither BNW or 1984 deny this, despite having fewer important characters. Offred's husband and daughter are her two anchors of meaning, but they slowly dissolve as she forgets them.

Like the System and the Party, the Religion has modern day precedents. Modern day, zealous social justice on campuses certainly has echoes of the Religion as it stifles opposing views. So does corporate culture, where networks are prescribed and interfaced with by cult-like appeals to greater powers. Obviously, the Religion exists in actual religious places like the theocracies of the Middle East or the theocratic towns and cities of the South.

Finally, the Religion also creates itself in a different way: The mold of a lot of dystopian novels has "The Chessmaster" at the end to reveal everything. We see this in not just BNW or 1984, but The Matrix, the Giver, probably the Hunger Games and other novels. The Chessmaster of the Tale isn't the Commander. It's nobody. Every individual in the Tale is swept along the current of all the other individuals. There aren't any master plans, but individuals fighting amongst themselves for power and survival. They create a planned dystopia, but nobody in particular wanted it the way it came.

The Handmaiden's Tale is a great book, and I could get into the "feminist" aspects of it, but I don't think it's actually that feminist. It is most anti-reactionary, and it predicted reactionary thought word for word (read some of the Commander's thoughts and then you'll see them in print, digested by hundreds of thousands, on /r/theredpill). I could also get into the historical precedents of it, but Atwood does that in an afterword for the version I read. I could get into the powerful writing and world building and scene setting and tell you how wonderful they are, but my header should've done that for you.

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Sunday, May 21, 2017

Review: A People's History of the United States

Zinn's book could be split into two: "A History of American Atrocities and the People That Fought Them" which would be an exhilarating, if sobering, read about the violence that made America, America. The other section would be "Boring Chronology of Protests and Strikes without Context." When Zinn tries to describe different strikes and protest movements, he simply states the absolute numbers and absolute history. He doesn't set the context. For example, he describes a protest of 200 people in Boston (I think). Sure, that's great. But I see a protest of 200 people every single time I go to get Indian food in Washington, D.C. These protests never appear anywhere in popular culture afterward.

The first book would be better, shorter, and more powerful. The second would be a good Wikipedia page.

The first book would be better, shorter, and more powerful. The second would be a good Wikipedia page.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Review: Group Chat Meme

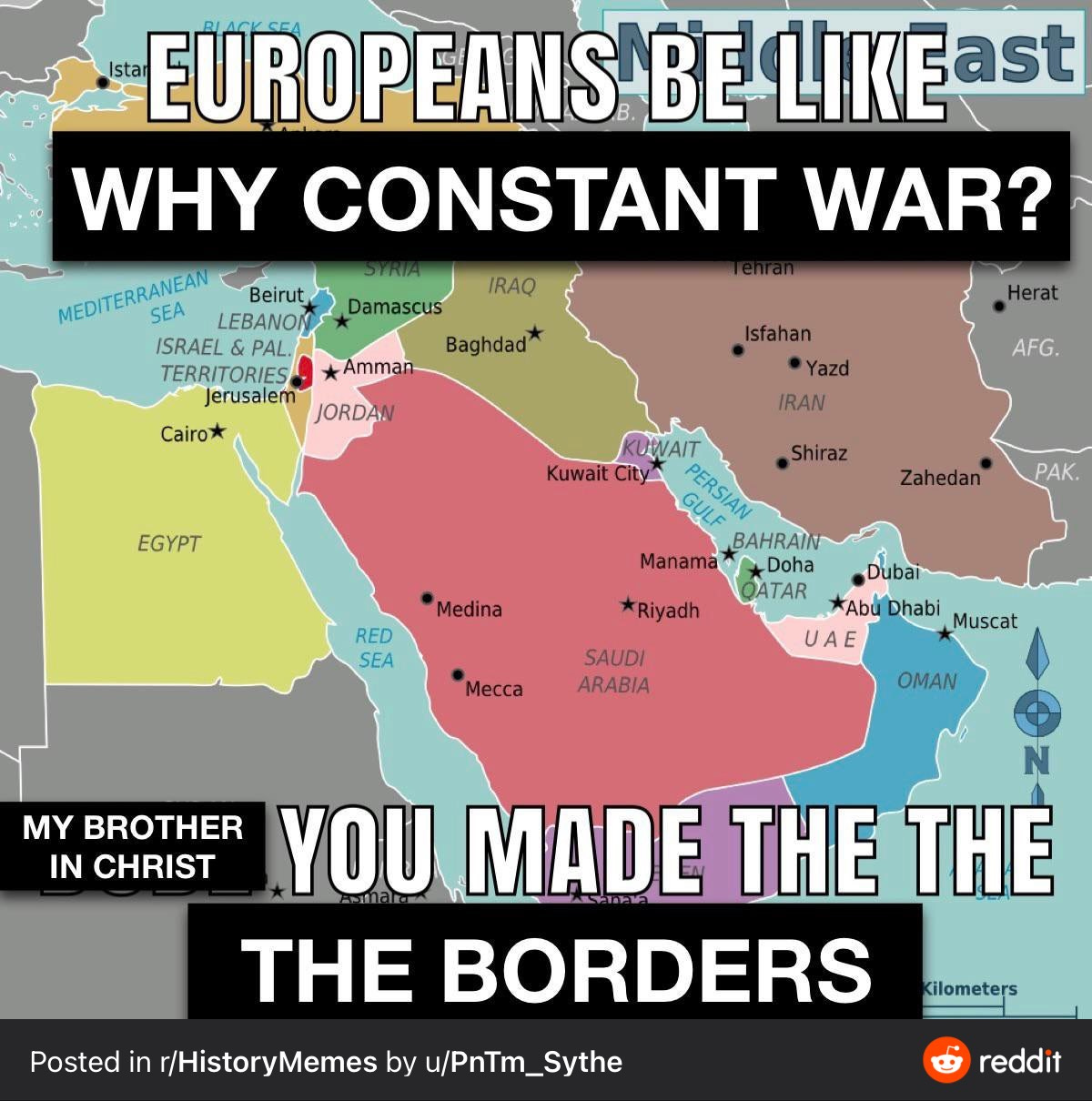

tl;dr: To endorse the concept that European borders are to blame for developing world conflict is to endorse problematic concepts of nationa...

-

I am intimately aware of the errors in my thoughts and the sins of my soul. I can hear the Type-A asshole screaming like a stolen mind in t...

-

People get the cosmic calendar wrong: The universe is not old. It is not old and wise and dirty. We tell that story to wrench dogmatic minds...

-

Uncommon Grounds is a great book, and points to what I think is an overlooked section of history: the history of things. We have lots of boo...