You cannot save the planet with "just a carbon tax". The math of climate change screams that at you. Even if you were able to wipe out $27 trillion in fossil fuel assets, there's already too much carbon in the air. We have created a peak carbon dioxide parts-per-million that humanity has never seen since we diverged from Chimps. We have to- as the title suggests- drawdown the very carbon in the atmosphere.

And yet, the possible solutions are all very politicized, at least in the United States. District heating and insulation regulations? Who cares if it decreases my heating bill, ain't no way the filthy liberal, commies are going to touch my air.

Reduced food waste? Eating more plants? God gave me those animals to eat and throw away as I see fit; ain't you read a Bibble?

There are ultimately two types of solutions: (1) decreasing/eliminating carbon output, or (2) pulling out carbon from the air. Of the former, there are three subtypes. (1.a) become more energy efficient, (1.b) replace carbon-based energy with a non-carbon based energy and (1.c) forgo a carbon luxury.

The solutions the book comes up with are, in general, wonderful. Any reasonable person would look at them and think, "Oh yeah, of course." A three-pronged approach by the government would easily force society to reorganize itself around these lines: You start with (1) a carbon tax to punish energy inefficiency, force people to give up carbon luxuries and replace their carbon-energy systems. You then (2) create a trust or government organization that the government partially funds with the carbon tax and (3) a strong, robust regulatory authority that is able to measure, collect, and analyze the carbon production of companies and other countries.

But the seeming reasonableness of these three over-arching solutions ignores the point: large sections of the population hate them on a moral level. Regulatory agency? Tax? Government trust? These are ideological non-starters. However, without them, there are no other solutions:

Silvopasture is the #9 solution. The tl;dr of it is"put cows into forests". But guess what? That costs money, and that cost is going to be baked into each pound of beef that the silvopasture produces. Then you have to figure into the fact that the entire world simply can't be turned into a cow forest! People will have to eat less meat, which they'll do... because why?

Each solution presented is ultimately the same: there is no reason for mass adoption (which is necessary for the solution to work) unless there is an external force to incentivize adoption. And, given that the market will only begin reacting to most of these forces when it is too late, there has to be an incentive force.... which we've already found to be politically blocked off.

Sure, some of the ideas are hazier and less market based: educate women! give birth control to the developing world! That doesn't save them from the toxic cloud of ideology that hangs over this whole situation though.

That's why Drawdown ultimately failed to be the great hope it was painted as. It's not so much a comprehensive plan as it is an assembly of ideas that would get implemented by the market in reaction to an outside force punishing it. Each idea is presented in a very simple way. A 2-3 page description of the solution and its carbon savings, net dollar cost and net dollar savings... but nothing about it necessarily scream, "This solution will work and pan out!" except for the solutions that were agreed upon before 2016.

This assembly of ideas does have hope. It does have the nuggets of hope. It says what we've always known: "We can fix this. It is possible." But it doesn't give us any hope at all that it is probable.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Wednesday, August 9, 2017

Review: Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II

The Slave Power was not defeated after the destruction of the Confederacy. It was sublimated. Like a radioactive piece of crust, the Slave Power was pushed under the earth, but it was never vanquished. It remained there, technically illegal, but it would strike on the roads or by the rails, and steal away with the black citizens of the South.

Was it dead? Was it a ghost? Pale. White. Bloodless but bloodthirsty. Having been skinned by America, the Slave Power killed the Law and wore its face; it desecrated its face forever.

Where did it steal away? To Hell. It pulled black souls into the lightless pits of Alabama's heart, into the red hot factories of Birmingham and Atlanta, and back onto the plantations of Florida. What did the Slave Power do? It threw "them into the fiery furnace, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth."

The Slave Power instituted what Blackmon describes as an "era of neoslavery". The laws were different, but the effects were the same. You had to accept your position on a farm, not get an education, ask a white master for permission to do anything... and if you left your farm or failed to ask your white master for permission, then the next white man to set his eyes on you could pay the sheriff to make you lawfully his.

Perhaps it was different: free blacks could be enslaved, and an enslaved black was an expendable resource to be pushed to the limit, not "capital" to be nurtured.

And yet, they were more differences: industrialization came to the South following the black soot of coal and iron. Imagine the rise in labor prices! Iron, coal, cotton! Imagine how the industrial giants, the plantation lords must have felt competing against one another to see their profits eaten away by the dirty, greasy, tan faces of poor whites and the free, brown faces of blacks.

You must imagine! For rather than facing losing their wealth, potential wealth, and power the Capitalists enslaved the latter group and pit the former against them. And the South helped. In Alabama, 75% of annual state revenue was, at one point, directly from slave buyers' payments. These laws were crafted by Confederate leaders to line their own pockets, build their empires, and to erect monuments to themselves in their capitals. And that is exactly what they did.

The Slave Power hides in plain sight with a tempting bottle of Purel. There is a desire to sanitize history; there has always been this desire. In the early 1900s, Theodore Roosevelt had to push back against a wave of revisionist white apathy who wanted to forget the Civil War was a war for and against slavery. In the early 2000s, we have to push back against revisionist white apathy, as well.

"Why has there continued to be wealth, income, and education gaps between black and white Americans into the 2010s?" It's a common question. It's an ignorant question. The answer is very simple: "Your grandmother was probably alive when some Southern blacks were being held in a state indistinguishable from slavery."

Whatever you thought Jim Crow was like, Blackmon shows that it was most definitely worse.

Was it dead? Was it a ghost? Pale. White. Bloodless but bloodthirsty. Having been skinned by America, the Slave Power killed the Law and wore its face; it desecrated its face forever.

Where did it steal away? To Hell. It pulled black souls into the lightless pits of Alabama's heart, into the red hot factories of Birmingham and Atlanta, and back onto the plantations of Florida. What did the Slave Power do? It threw "them into the fiery furnace, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth."

The Slave Power instituted what Blackmon describes as an "era of neoslavery". The laws were different, but the effects were the same. You had to accept your position on a farm, not get an education, ask a white master for permission to do anything... and if you left your farm or failed to ask your white master for permission, then the next white man to set his eyes on you could pay the sheriff to make you lawfully his.

Perhaps it was different: free blacks could be enslaved, and an enslaved black was an expendable resource to be pushed to the limit, not "capital" to be nurtured.

And yet, they were more differences: industrialization came to the South following the black soot of coal and iron. Imagine the rise in labor prices! Iron, coal, cotton! Imagine how the industrial giants, the plantation lords must have felt competing against one another to see their profits eaten away by the dirty, greasy, tan faces of poor whites and the free, brown faces of blacks.

You must imagine! For rather than facing losing their wealth, potential wealth, and power the Capitalists enslaved the latter group and pit the former against them. And the South helped. In Alabama, 75% of annual state revenue was, at one point, directly from slave buyers' payments. These laws were crafted by Confederate leaders to line their own pockets, build their empires, and to erect monuments to themselves in their capitals. And that is exactly what they did.

The Slave Power hides in plain sight with a tempting bottle of Purel. There is a desire to sanitize history; there has always been this desire. In the early 1900s, Theodore Roosevelt had to push back against a wave of revisionist white apathy who wanted to forget the Civil War was a war for and against slavery. In the early 2000s, we have to push back against revisionist white apathy, as well.

"Why has there continued to be wealth, income, and education gaps between black and white Americans into the 2010s?" It's a common question. It's an ignorant question. The answer is very simple: "Your grandmother was probably alive when some Southern blacks were being held in a state indistinguishable from slavery."

Whatever you thought Jim Crow was like, Blackmon shows that it was most definitely worse.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Review: Group Chat Meme

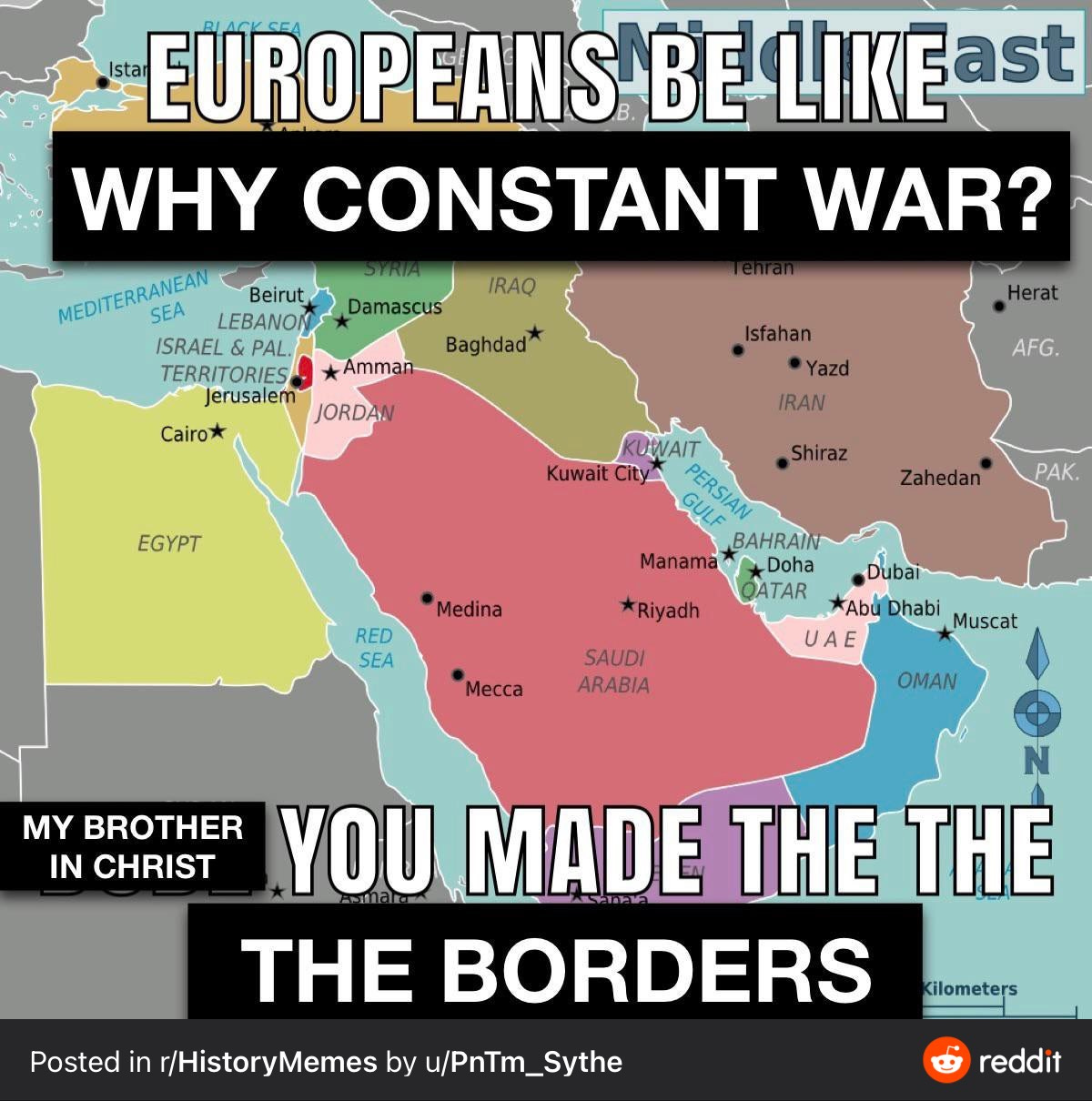

tl;dr: To endorse the concept that European borders are to blame for developing world conflict is to endorse problematic concepts of nationa...

-

I am intimately aware of the errors in my thoughts and the sins of my soul. I can hear the Type-A asshole screaming like a stolen mind in t...

-

People get the cosmic calendar wrong: The universe is not old. It is not old and wise and dirty. We tell that story to wrench dogmatic minds...

-

Uncommon Grounds is a great book, and points to what I think is an overlooked section of history: the history of things. We have lots of boo...