It is incredibly hard to read history without thinking, “The British Empire was the worst political organization in the history of the planet.” And yet, Why Nations Fail, at least partially, absolves the British Empire of leaving their former colonies politically broken and destitute. It turns out that the natural equilibrium state of humans in a state is politically broken and destitute.

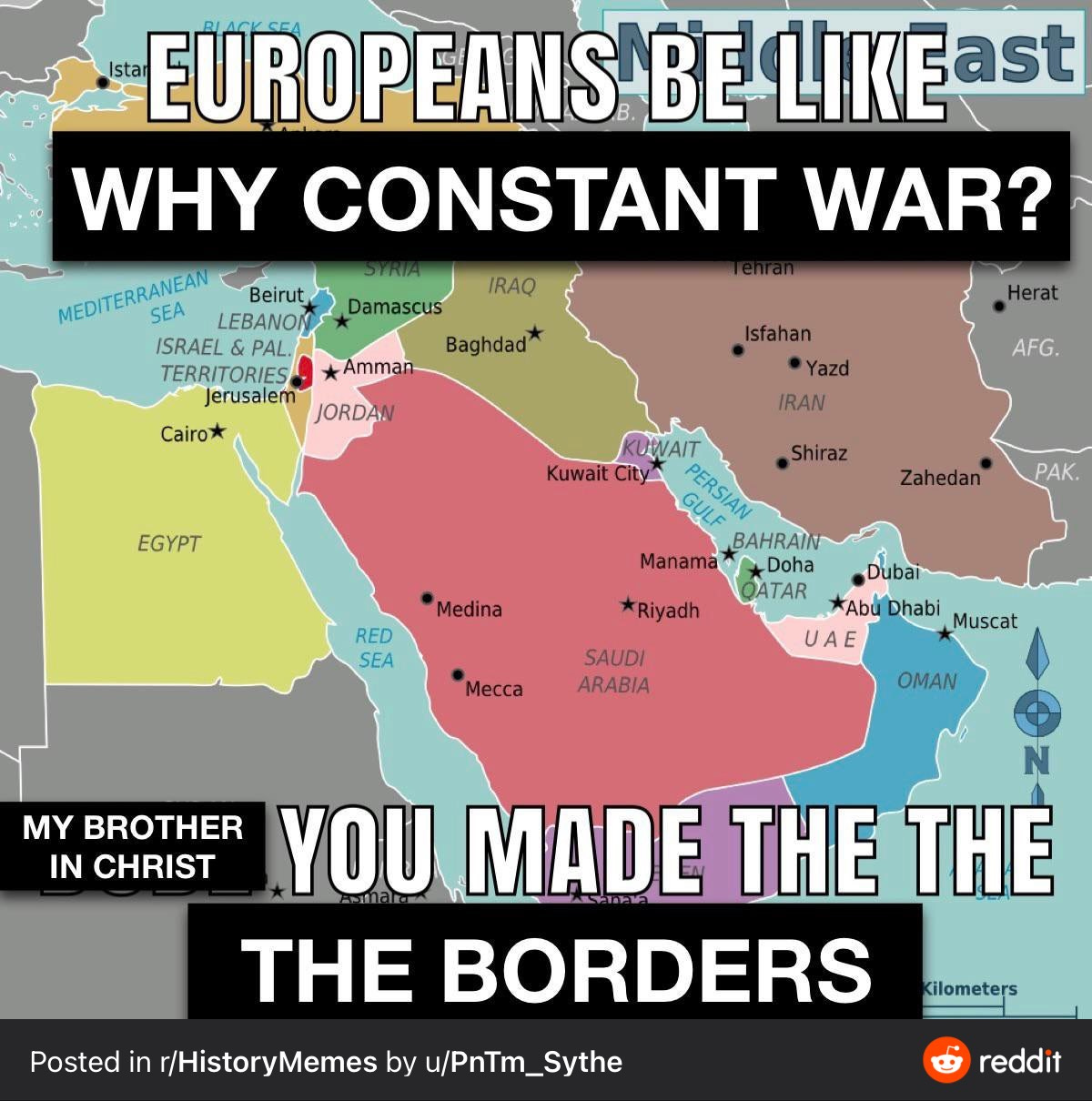

The British didn’t enact regimes of tyranny over democracies abroad- they simply replaced local rulers with their own officers, and instead of directing the local resources to a few local elites, directed them towards the home isles. This pattern happened in other European empires, dating all the way back to Spain’s conquest of Central and South America. This pattern happened in the gunpowder Empires. This pattern happened in the Asian empires, the African empires, the American empires, and all the tiny states trying to be powers throughout all of history:

The British Empire was the worst political organization in the history of the planet, because it was the culmination of _extractive_ political organizations.

I bring up the British Empire because people like to point at the British Empire and blame it for post-colonial troubles, and others like to point at it for post-colonial good fortune, but what Acemoglu and Robinson make clear is that rulers may come and go, but _instutitions_ guide the progress of peoples.

Their story goes like this: There are extractive political institutions- states and leaders that collect rents from other people- and there are extractive economic institutions- the ability to steal land from subordinates or slavery or monpoly over a rare good. These two institutions are mutually reinforcing- the political institutions use force to protect the extractive economic institutions, and the economic institutions pay off the political ones.

These institutions are the answer to “Why Nations Fail”: there is a status quo bias. Political and economic leaders in extractive states _don’t want to succeed_, because if they do they will lose out on their political and economic power. When they do attempt to succeed, it’s mostly an effort to continue their own survival.

The opposite types of institutions- inclusive institutions- tend to bring about the opposite effect, and they too are self-reinforcing. An inclusive political institution is pluralist, with power located at multiple competing nexuses and flowing to new centers of power as they form. An inclusive economic institution is diversified across different types of capital, and fortified by stable property rights. The incentives in this system are against the status quo- and directed towards profit and growth.

The physics of why nations fail can be boiled down to this: is a historic event distributing power more broadly, or centralizing it in the hands of some clique.

The history of nations failing (or not failing) is a lot more fascinating! Acemoglu and Robinson walk us through case study after case study, from the history of Latin America to Japan to various African countries. They tell of the internal dynamics of Argentina causing it to plummet from First World to Second World and the complicated but romantic history of Botswana as it moved from Third World to Second World against all odds. The historical snapshots in this book are enough to recommend it.

Yet, the physics of the book seem quite simplistic, because they are. 1) Acemoglu and Robinson only talk about “growth” as if it were the adoption of technology, not the _creation_ and invention of technology. 2) They only interact with the history of post-plague states, and their theory has nothing to say about Bronze Age states or earlier (is a hunter-gather society inclusive?). 3) Inclusive states have existed every once in a while historically, yet not produced the same economic explosion as England’s industrial revolution, why is that? 4) Other explanations from the Great Divide seem coherent, and yet Acemoglu and Robinson throw them aside. “It’s only the institutions” they say on every page, yet The Origins of Political Order by Fukuyama breaks down institutions into more constituent parts, and those parts definitely _add_ explanatory value.

One of the things that get me is that the dynamics Acemoglu and Robinson describe are of two separate equilibriums, two self-reinforcing cycles, but they don’t mention the natural factors that push a society from one to the other unless it’s good for their story, but those natural factors entirely rely on the factors that they denigrate. “Geography has nothing to do with development” doesn’t mean much if geography makes it a lot easier to be inclusive (Greek city-states) or extractive (Deep South America).

Institutions obviously have a powerful role in the development of societies, and they may even be dominant, but they themselves are contingent on natural, geographic, climactic, cultural, and technological factors.

What actionable advice can we take from this theory? The propagation of inclusive economic institutions is the main key: private property rights, IP rights, equitable law enforcement, the rights of labor, and the restrictions of gross centralization of economic power are all ways that political interests become diffuse and pluralistic while also centralized and incentivized to be engines of growth.

In other words, we have to vote for Biden.