When you read the Bottom Billion, something seems off. The plight of the poor in the developing world is known to all who read about it just a little bit. There is rampant starvation, intranational and international conflict. Africa is full of terrorists waiting to fly to Mexico and walk across the American border. Christian missionaries, setting flight to go … build schools…?... lead the battle cry, “We gotta help them”.

Paul Collier’s 2007 book, “The Bottom Billion” attempts to be a guide to helping them. Since it’s publishing, something must have. The World Bank reports the extreme poverty rate has dropped from 18% (2008) to 10% (2015). That’s a 44% reduction in just 7 years. Further, the World Bank data tells us that the intensity of poverty has decreased.

If you had a magic money printer (or a tech start up) in 2008, it would have cost ~$250 billion a year to bring everybody under the poverty line up to the poverty line. In 2013, it was only $160 billion.

“Money isn’t everything, Aaron” I hear you say. Correct, that’s fair. In 2007, almost 36 countries had life expectancies below 60 years, but in 2019 that number was 5. The number of countries with women having more than five children- a sign of not being able to control one’s family size, and hence women’s rights- has dropped from 35 to 13.

The gist of the Bottom Billion is that there are a billion people in numerous countries- most in Africa, with a few in central Asia and one or two in South America- that face extreme poverty that is so intense that they may be trapped there effectively forever. Paul Collier describes a horror world where 7 billion people in relative affluence live aside 1 billion people in extreme poverty (who also generate terrorists). And yet, when I comb over the data I can’t find a “trapped” population. Indeed, the countries that are in the most dire straits in 2020 -Syria, Venezuela, Oman, Libya- would not be considered in the bottom billion almost 14 years ago. Subsaharan Africa’s economy in 2017 was 14% higher than it was in 2007. That isn’t as brilliantly fast as Asia, but it isn’t slouching and is made of several countries, like Ethiopia (population: 100 million), where the GDP per capita has doubled.

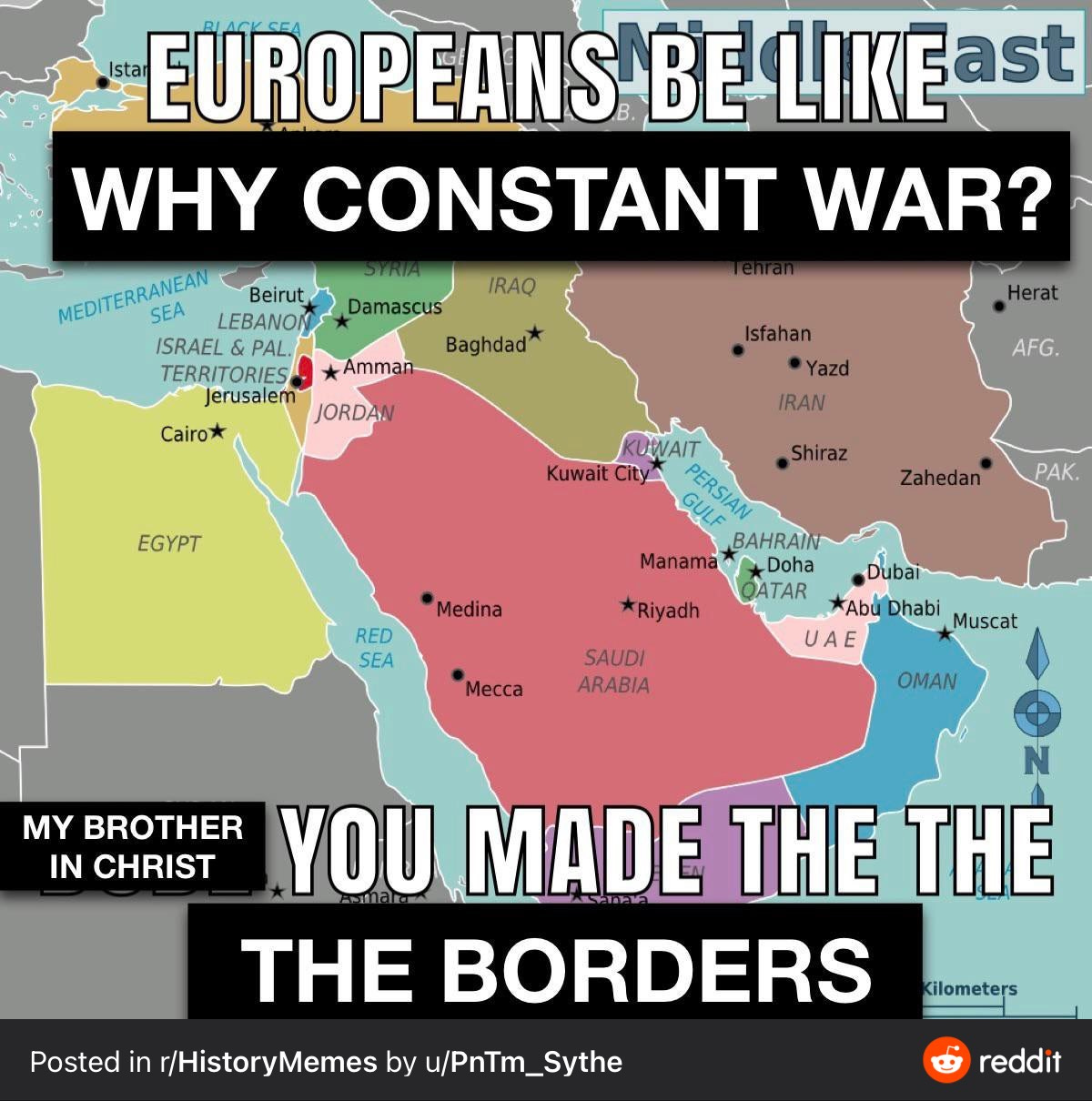

Paul identified four traps that were supposed to make these countries stay poor. These are Conflict, Landlockedness, the natural resource trap, and being tiny. Of these, when I look at a map of countries by economic success in the last decade, I mostly see “Did they have a war or something like a civil war?” Indeed, the Great Lakes region of Africa is pushing forward even in the countries that are landlocked. Are the other traps a component in slowing down economic growth? The natural resource trap definitely seems to compete with manufacturing in Africa, but who is having massive growth on the world stage seems to be dominated by proximity to China more than anything else.

The Bottom Billion list, as Collier identifies, has GDP per capitas about 30% higher on average in 2017 compared to 2007.

The four solutions described to help assist are directed aid, military intervention, international charters that encourage good governance, and trade policy. As far as I am aware, the latter hasn’t occurred in Western countries, and the military intervention that has happened was either an abject failure (Libya, Syria) or highly questionable (French troops sexually assaulting host country nationals). It does seem, however, that international charters have been functional. The African Union, which Collier does point to as an area of interest, has likely decreased the amount of military unrest throughout Africa, and the East African Community is likely the fastest growing economic region outside of Asia and Ethiopia. Setting international norms and tying them to incentives works.

Of course, given how tiny and technical some of the four solutions can specifically drill down to, I may not know that they’ve been implemented at all!

The book itself is well-written, the logical steps it takes you on seem valid, and the studies that make each trap seem reasonably backed by data, but the decade since it was published make it seem a bit quaint. References to terrorism and a quietness about China’s rise make it seem like a product of its time. Indeed, China is treated as a competitor to low wage labor, not the country beginning to suck up every raw material atom on the planet.

Anybody who still sees Africa or Central Asia or any historically poor region as still poor, or trapped in poverty, simply hasn’t looked at the data. They may be last in line, but unless they’re at war with themselves, they’re not stuck there.